Book review: The Aftermath

For the families of those sent to administer Hamburg in 1946, that strange people lived in an even stranger city – one in which, in July 1943, more bombs had fallen in just one week than fell on London in the entire war. On one night, so many incendiaries fell that a firestorm flattened eight square miles of Hamburg, its roaring 1,000-foot tower of flame sucking the air out of bomb shelters and sweeping up anyone still on the streets in its 150mph winds.

From such horrors – and those of the concentration camps nearby – how could there ever be a way back?

Advertisement

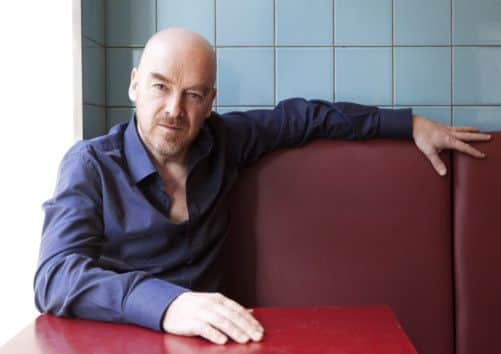

Hide AdThat is the background to Rhidian Brook’s novel The Aftermath – soon to be turned into a feature film by Ridley Scott’s production company – but it is only part of the story. The heart of it is based on an intriguing chapter in his own family history.

As a child growing up in Wales, he had always been proud of his grandfather Walter. And with good reason: this was a man who, at the end of the First World War had fought alongside Lawrence of Arabia. At the end of the Second, he was a colonel entrusted with the administration of a huge tract of countryside north-west of Hamburg.

All that was part of family lore, because in 1946 Col Brook had sent for his wife and three children to come and live with him. All other high-placed British officials in occupied Germany had requisitioned large houses for their families, but Col Brook was different. When he was shown the mansion selected for him, he allowed its German occupants to stay on there. They would share it, he decided; victors and vanquished living in harmony together, the very model, he hoped, of the new country rising from the ashes of the old.

Rhidian heard more of the story from his father Anthony, who was eight when he arrived in Hamburg’s Dammtor station and was driven through the shattered city “When my father told me, I thought what a great set-up for a novel it would be – a British family sharing a house with Germans just one year after the end of the war. I haven’t yet found anyone else who did the same thing. If anything, the decision to share a house was slightly frowned upon.

“But what hooked me was realising that, because of the war, my grandmother Anthea hadn’t seen my grandfather for a long time. And there was a certain resentment about having to go to Germany and to share a house with former enemies. I realised that this wasn’t just the story of a reconstruction of a country, but it was probably also about a reconstruction of a marriage.”

Three years ago, he was in the office of Ridley Scott’s film production company. He had planned to pitch three different ideas. Instead, he found himself talking about what a great film could come out of out that interplay between rebuilding a marriage and rebuilding a country. “That’s it!” the producer told him. “I don’t want to hear any more ideas. I want that one!” (A smart move, as it turned out: not only had Ridley Scott’s own father been involved in postwar reconstruction in Germany, but later the head of Universal read the novel on a plane to LA, loved it, and came on board as well.)